Daniel describes here his highlights from the ISCB 2025 conference in Basel, Switzerland, which took place 24-28 August 2025.

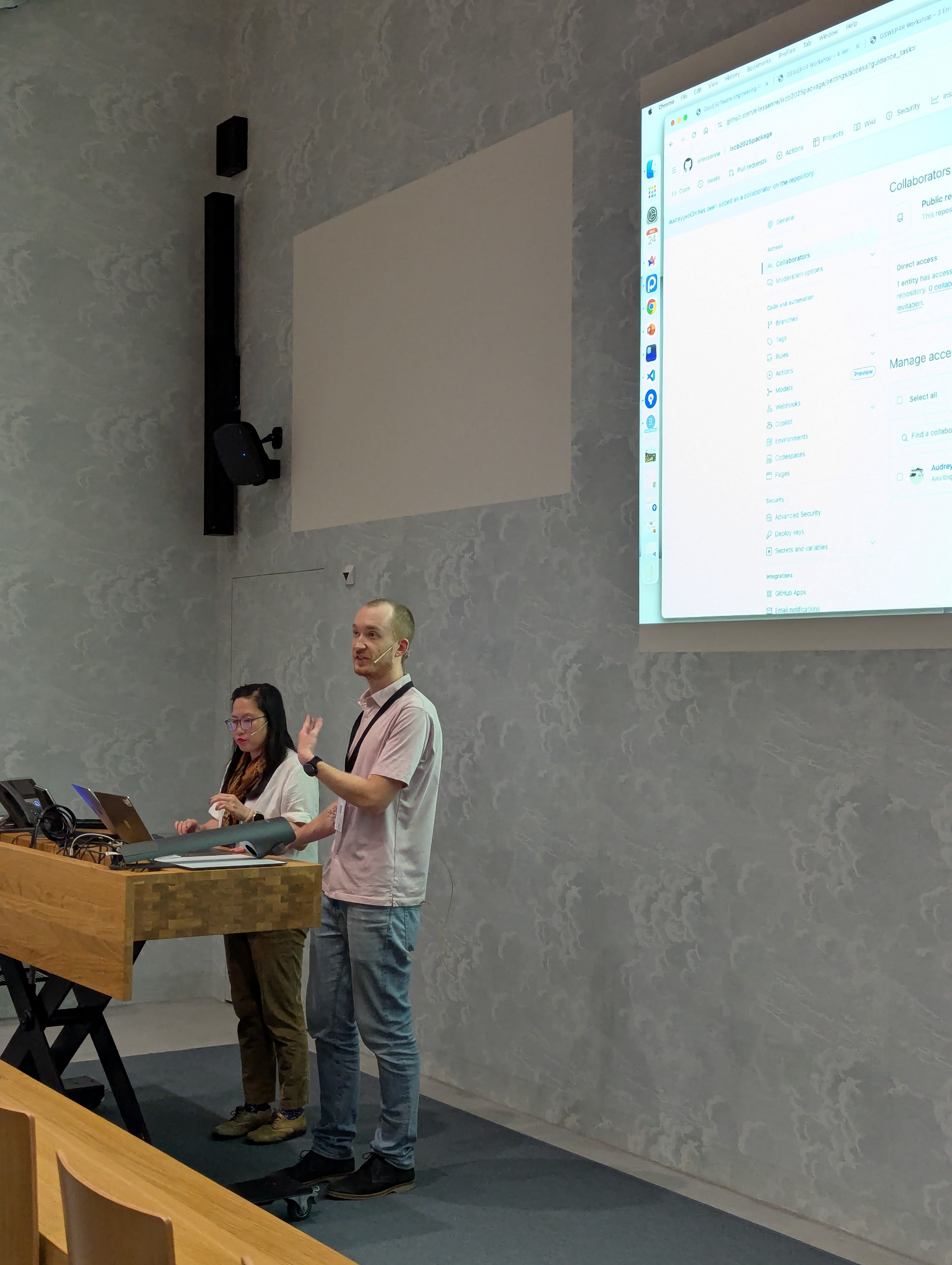

Another GSWEP4RP workshop

On the Sunday, Alessandro, Audrey and I held another successful edition of the “Good Software Engineering Practice for R Packages” workshop as a pre-conference short course. As usual all materials are open source available, see here. It was yet another great openstatsware team effort, and we had a lot of fun preparing and delivering the workshop - and the feedback was again very positive!

Opening session

On the Monday the conference opening session announced the record number for an ISCB conference of almost 900 in-person participants! This underscores the amazing work that the more than 30 people large organization team achieved.

Note to myself was that the David Spiegelhalter book “The Art of Uncertainty” was given as a present to the opening speakers - probably something to read in the future.

Noteworthy was also Hans Clevers short opening presentation - he has been leading the pRED (early phase research) department at Roche for a couple of years now. He shared that he had still written his PhD thesis on a typewriter - something that is hard to imagine for most of us nowadays. So much has changed in the last couple of decades. With the microarray technology, computation became very important in biology (a topic that I still remember from my genomics courses at LMU Munich almost 20 years ago!) He summed up that biology has changed dramatically. It is the “outcome of randomness” and there are very few natures of law if you compare with sciences like chemistry and physics. He also mentioned that politics has become a key concerning topic for the pharmaceutical companies. Where they maybe had a politics update every half year or so in the past, now it was every week at least.

Opening keynote

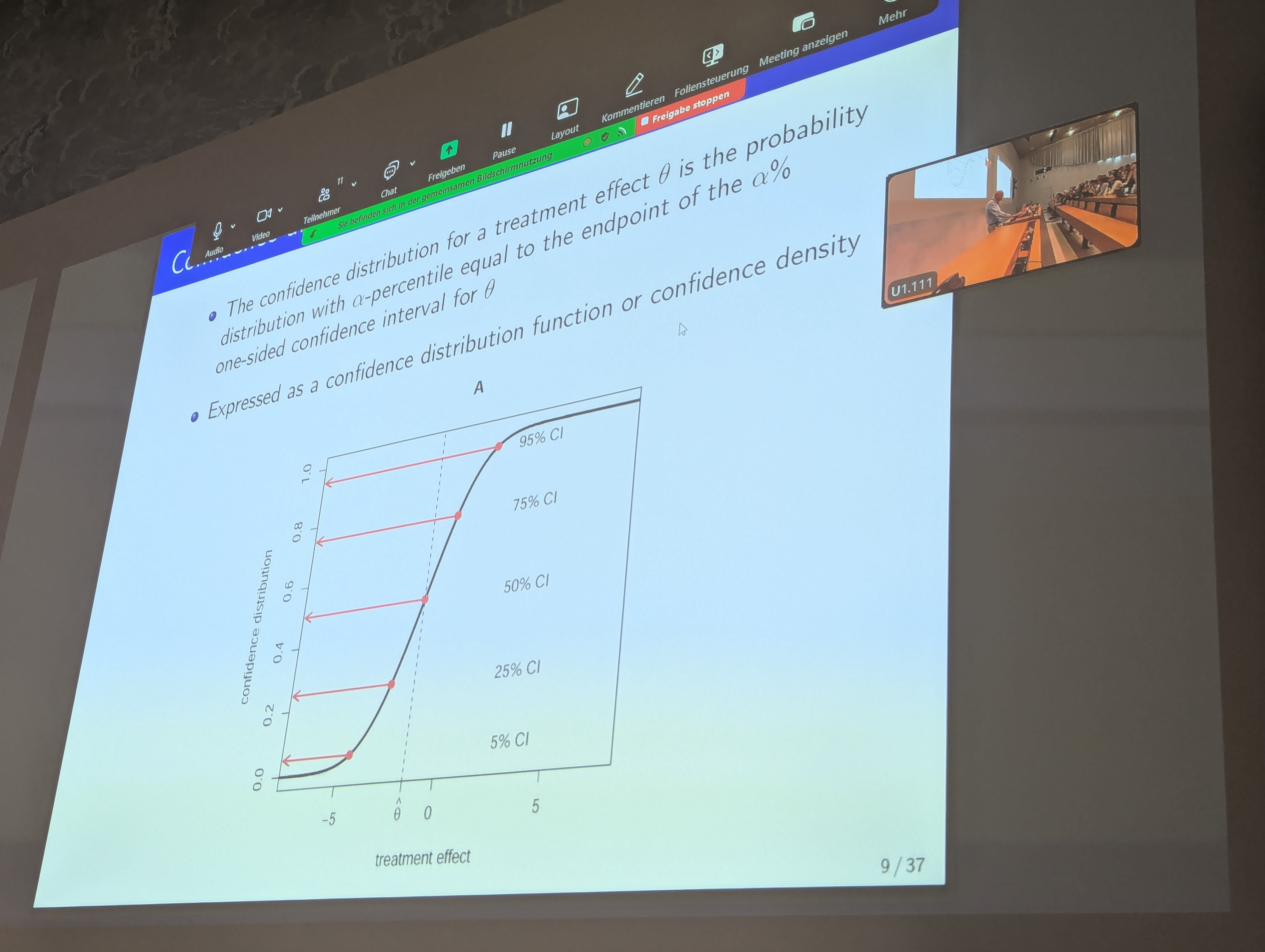

Ian Marshner from the University of Sydney gave an inspiring keynote presentation about confidence distributions. The topic is not new, but has received renewed interest in the last years. An interesting reference is the Nature paper by David Spiegelhalter (again he comes here!) “Why probability probably doesn’t exist” (open reprint link).

Probability has two faces:

- randomness (“aleatory probability”) - corresponds to frequentist inference

- lack of knowledge (“epistemic probability”) - corresponds to Bayesian inference

This has been long studied by many philosophers (e.g. Ian Hacking). Confidence distributions allow to have both frequentist and Bayesian inference, because they introduce Bayesian features into frequentist inference. The book “Confidence, Likelihood, Probability: Statistical Inference with Confidence Distributions” by Hjort and Schweder (link) gives a thorough presentation of the theory and applications of confidence distributions.

But it is an older concept: Sir David Cox already in 1958 proposed the use of confidence distributions in his paper “Some Problems Connected with Statistical Inference” (link). R. A. Fisher also had fiducial distributions, which are related.

Ian Marschner now wrote a Statistics in Medicine tutorial (link) where he promises in the title “posteriors without priors”. Indeed, confidence distributions can be used to derive posterior-like distributions without the need to specify a prior - however they still “only” convey the frequentist properties of the parameter estimates.

In the discussion, several connections of confidence distributions to other statistical concepts were highlighted. For example, if you use a likelihood confidence interval and a flat prior, then in some cases the posterior distribution and the confidence distribution will be identical. I understand that a paper by Fraser (link) discusses several of these connections. On the other hand, the idea to still introduce a prior distribution and combine that with the confidence distribution to a hybrid posterior distribution seems not to have been discussed in the literature yet.

Marshner also discussed several applications in group sequential designs, and mentioned that they are currently developing an R package “CONFadapt” to implement the proposed methodology (it seems not to be available anywhere yet).

Posters

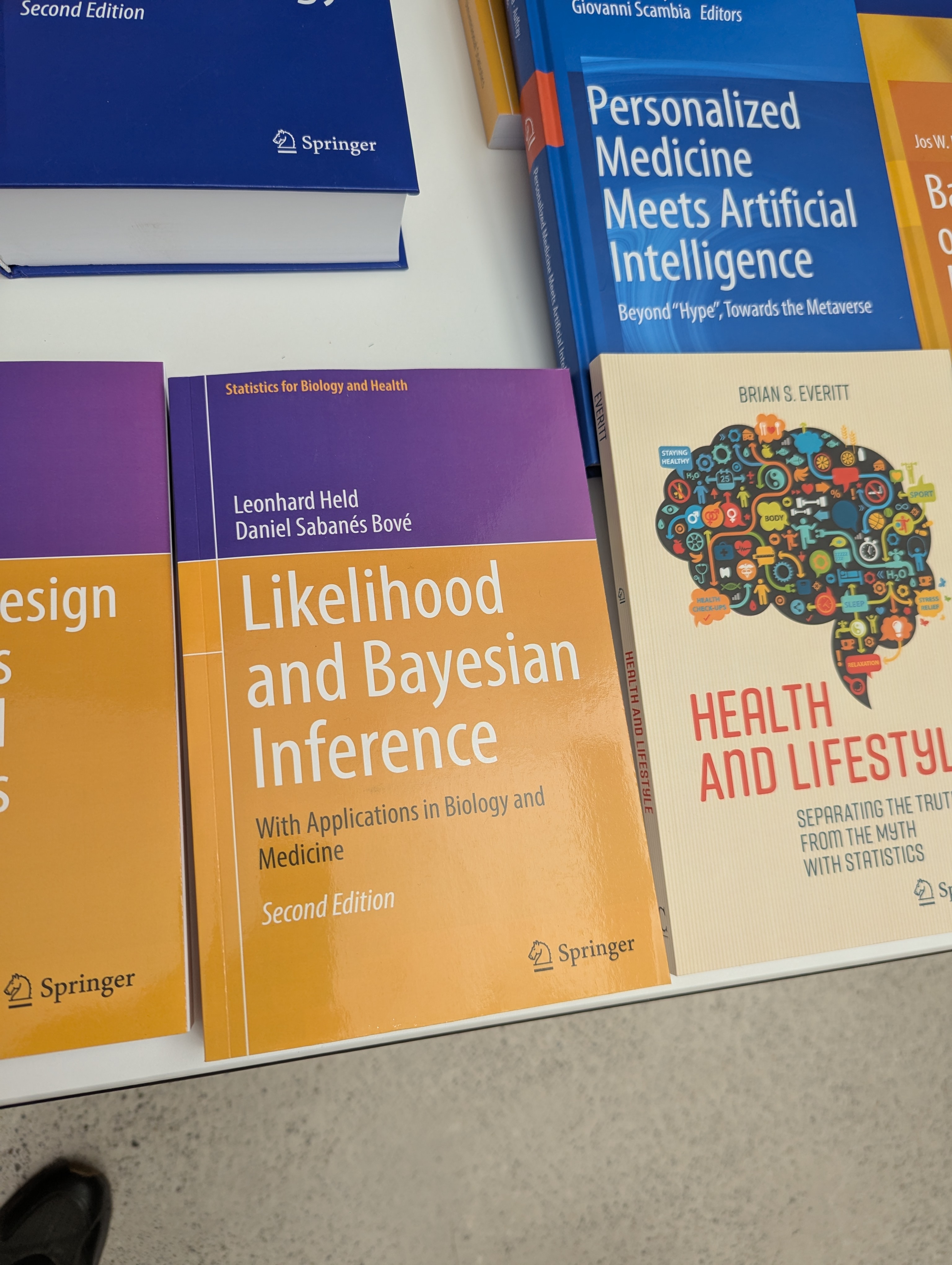

Lots of posters were presented, and I was one of the presenters - I shared an overview of the R packages rpact and crmPack for clinical trial design in R (see the poster here). It was a bit unfortunate that the food was far away from the posters, and there was no dedicated poster session. Therefore I did not get too many poster viewers. However it was fun to have a raffle to win a first edition copy of our “Likelihood and Bayesian inference” book - finally a good use of the book that just stood in my shelf for the last years! Plus it was nice to see that Eva Hiripi from Springer had our second edition on offer at the Springer booth.

Presentations

There were many interesting presentations, and I cannot summarize all of them here. A few highlights for me were:

- MAMS selection design by Babak Choodari-Oskooei. He evaluated different MAMS designs which start with e.g. 4 active arms and 1 control arm, and then drop arms based on interim analyses: e.g. drop the worst arm at each of 3 interim analyses and then perform the comparison with control of the surviving arm at the final analysis. He found via simulation studies that you should not select too early or too hard in order to obtain good operating characteristics. The corresponding (open access) publication is here.

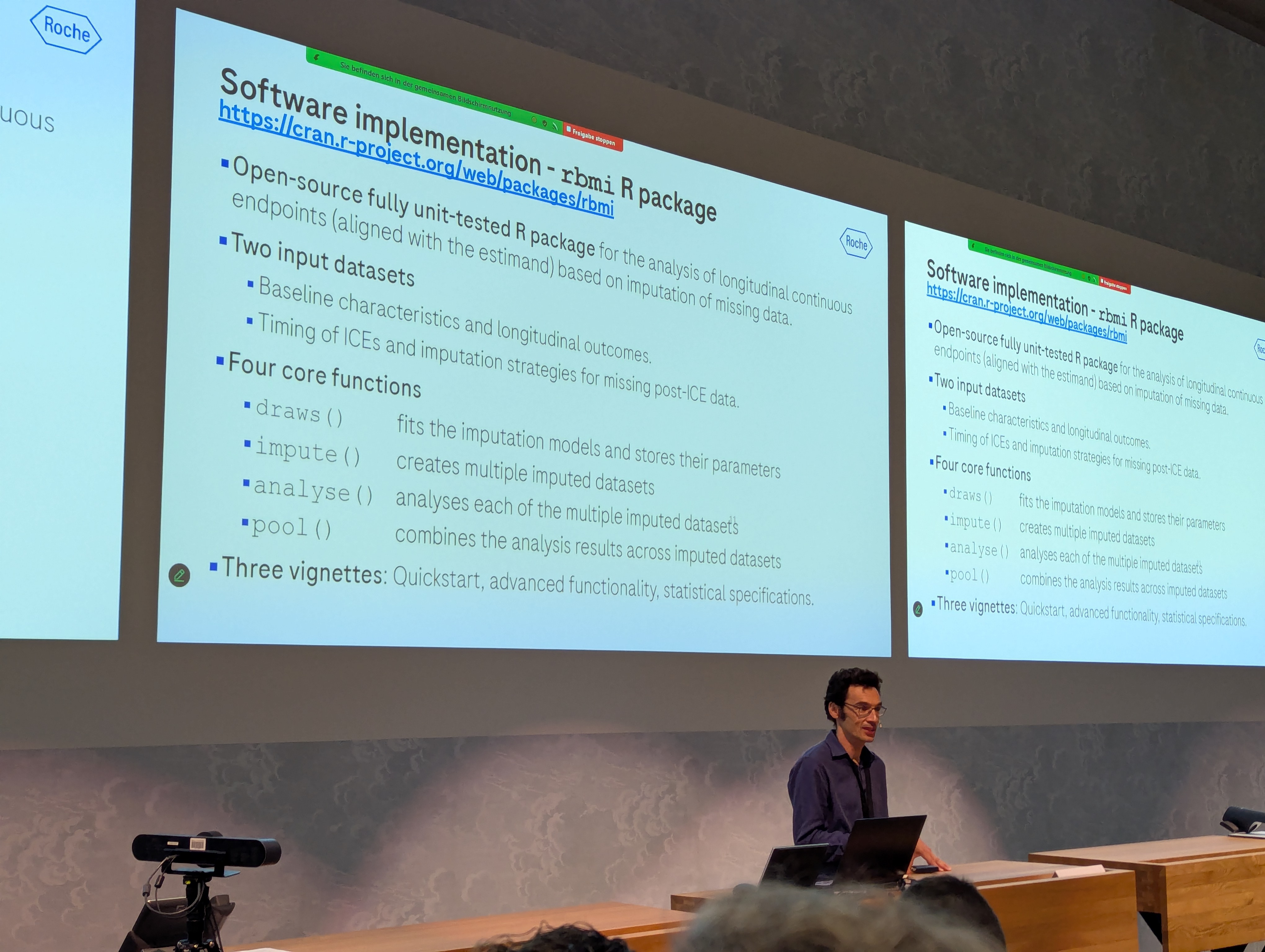

- Bayesian analysis of the causal reference-based model for missing data in clinical trials by Brendah Nansereko. She combines the reference based multiple imputation approach with a causal inference framework: For example, the causal model could postulate that the effect at a later time point is a certain fraction of the treatment effect at the time of discontinuation of the active treatment. The treatment effect is then estimated under the causal model using Bayesian inference, assuming a prior on the fraction beforehand. This topic is interesting because I have been involved in the

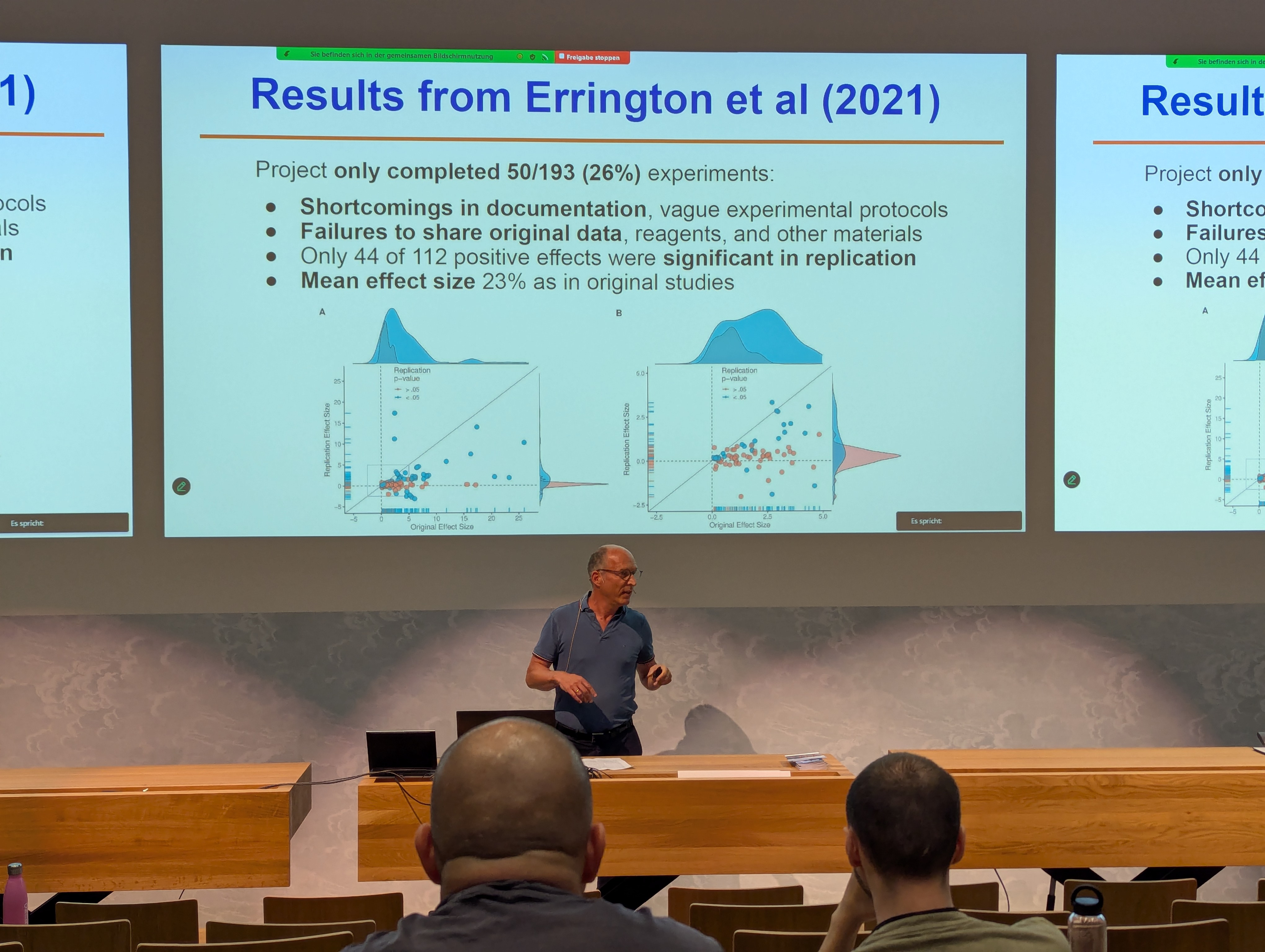

rbmiandmmrmpackages and Marcel Wolbers and Jonathan Bartlett are the supervisors of the project. - Questionable Research Practices by Leo Held was a sobering and sometimes shocking presentation. De Vrieze found that 1 in 12 Dutch scientists was involved in fraud (link). There are minor and major errors or QRPs. Positive developments are that e.g. the Molecular Brain Journal Editor says “No raw data, no science” and only 1 in 41 submissions had submitted sufficient raw data. Reliability projects in preclinical cancer biology has contracted independent labs to try to reproduce results: Only 1 in 4 projects could be completed at all. This is an illustration of the “translational valley of death”. Leo continued with the Eliezer Masliah scandal from 2024: he had fabricated more than 130 papers over the course of his career, and some of these led to failed Phase 2 trials. Another shocking trend are “paper mills”, which produce fake papers for a fee (see here for a background story on this topic).

Leo closed with key lessons:

- Be rigorous in your own research: Always share FAIR data and code, and follow simulation study guidelines.

- Avoid QRPs in collaborations: e.g. push back on QRP requests, and pre-register studies wherever possible.

- We need a science quality discipline, e.g. Szabo at the University of Fribourg advocated this already, see his interview here.

Chasing Shadows: How Implausible Assumptions Skew our Understanding of Causal Estimands

Kelly Van Lancker’s message was that sometimes, implausible assumptions of the causal model or inference methodology can be difficult to understand and therefore easily mislead.

She started from a simplified roadmap for causal inference:

- scientific question, which is translated to a model-free estimand

- link this to the data, be clear and critical about required assumptions

- Estimate this estimand, where you should take into account the feasibility of the estimation method

She discussed as one example the paper “A General Framework for Treatment Effect Estimators Considering Patient Adherence” by Qu et al (link), who use a principal stratification estimand to correct for time-dependent adherence when analyzing the treatment effect on the outcome.

One assumption made is the “ignorable adherence assumption”, which is not the typically used ignorability assumption made. So this is problematic, because adherence should have a causal effect on the outcome. She described an alternative assumption, which would though have significant consequences on the estimation approach: You would have to only include patients which adhere to the treatment effect. It was interesting to see the usage of so-called single-world intervention graphs (SWIGs) to illustrate the causal assumptions made.

Another problematic assumption made was the “cross-world” assumption that adherence under potential treatment is independent of adherence under potential control, conditional on baseline covariates. This is a cross-world assumption because you cannot observe both potential outcomes for the same patient. The problem here is that the baseline covariates would need to be able to predict all plausible post-baseline data, which would however contradict that the adherence has an added impact on the outcome.

She argued that we have to:

- assess the plausibility of the assumptions made (important here is to come up with examples where the assumptions are plausible, but also examples where the assumptions would not be plausible)

- focus on less ambitious estimands

- focus instead on actionable estimands (e.g. dynamic treatment regimes in this application)

Adaptive design ICH E20 draft guidance

Frank Pétavy (EMA) summarized the current status of the draft guidance on adaptive clinical trial designs, which is currently in Step 2 (public consultation, until end of November 2025). The final step 4 is expected only in October 2026.

He explained that the final ICH guideline will become an EU guideline, however this does not have legal force in the EU (in contrast to the US with FDA guidelines e.g.). Alternative approaches are still possible, but need to be properly justified: The guideline states accepted standards, describes clearly the conditions for accepting proposals, and also explains how to argue for deviations from the guideline proposals.

He recommends to start reading with section 4 (“types of adaptations”) and then go back to section 3 (“key principles”). The question currently is whether the text is clear enough for using it in practice. The guideline discusses that “[the justification for adaptations] should weigh the advantages of the design against the extent to which the adaptations being considered add uncertainty about the trial’s ability to produce reliable and interpretable results”. One question Frank raised here whether this only depends on the “ratio” or also on the “absolute” values of the advantages and the added uncertainty.

Key principles discussed in section 3 are:

- Control of the type I error rate

- Provision of reliable treatment effect estimate (i.e. with limited bias), because the clinical assessor will mainly look at the estimates

- Not too many (different) adaptations

- Maintain integrity and blinding of the trial

Section 4 has reached the draft text consensus more easily. Frank asked whether readers would like wider or narrower scope of the treatment end / trial conduct compared to the EU reflection paper, and invited to make comments on this aspect. Generally, comments should focus on the content, and comparison with the EU concept paper, whether the right amount of detail is given. Also the connection to later produced training materials can be considered already now.

Frank also mentioned that historical borrowing is often a discussion between the statistician and the clinician - both on the assessor’s and the sponsor’s side. It is important here to speak the language of the clinicians for these discussions. Non-concurrent controls are not in the scope of the E20 guideline.

Summary

This was a really great conference! I could have written much more here but it just takes a lot of time to write this down in a nice way - that is why I only got to it now, more than 5 weeks after the conference. There were many other highlights, most of all meeting a lot of colleagues and friends from Basel and beyond. It was great to see many people in person who I have only seen in video calls before! Plus the weather was great, the social program was engaging - I could visit the Novartis campus with an architecture tour, and the conference dinner was a lovely barbecue at Grün 80. Hope to be back again at ISCB 2026 in Freiburg, Germany!

rbmi was prominently mentioned by Paul Delmar